Why Doesn’t Justice Kagan Just Run for Office?

The Supreme Court is the wrong place to worry about public sentiment.

Justice Elena Kagan is warning that the Supreme Court’s insulation from public whims threatens our democracy, but this is the court’s role by design, and eroding it is the real danger to our liberties.

Last week at a judicial conference, a moderator asked Justice Kagan about public confidence in the high court. The number is at its lowest — 25 percent — since Gallup first began polling the topic 50 years ago.

The justice responded not with a defense of the institution or an explanation of why she and her eight fellow members have lifetime appointments rather than standing for election, but by accepting the underlying premise.

“If over time,” she said, “the court loses all connection with the public and with public sentiment, that’s a dangerous thing for a democracy.”

After allowing that the court has a vital function in our republic, Justice Kagan repeated the point, concluding, “So that’s why the legitimacy of the court is so important.”

The quality of “legitimacy” invites further analysis. The Constitution sets up three, co-equal branches of government. Two of those — the bicameral legislature and presidency — are answerable to the public at the ballot box.

If individual justices wish to influence policy, they are free to run for office. Otherwise, since Congress sets up the Supreme Court and confirms new members nominated by the president, it’s only through those elections that citizens can influence it.

This includes on issues such as the two thirds who, according to an AP-NORC poll conducted this month, favor term limits and mandatory retirement ages for justices.

It’s also worth noting that Gallup only began polling about the high court after its 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling, which even a liberal like Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg judged had inserted judges into the realm of politics where they did not belong.

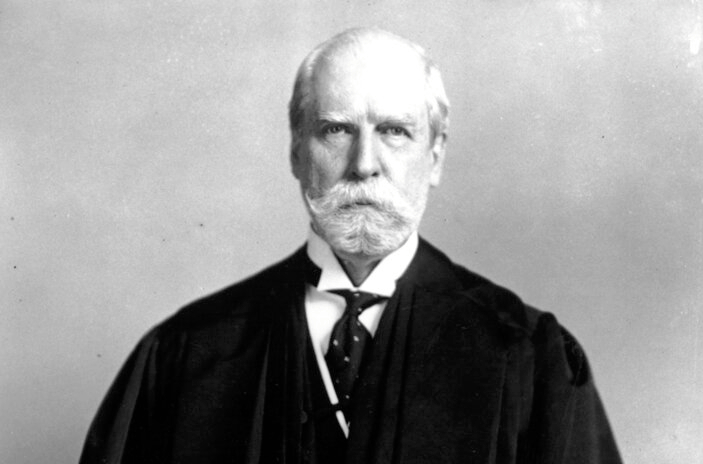

In 1916 another associate justice, Charles Evans Hughes, felt the tug of party politics, too. So he did the only thing he could. He resigned from the bench and stood for election.

When the Republicans nominated Hughes for president, the Sun reported that there was unease at the Chicago convention. Could he make the transition to the temperament of a campaigner from that of a sober judge?

“A great man, a great intellect,” the Sun quoted delegates as saying of the former New York governor, “but he hasn’t got the stuff that appeals to the ordinary voter. He’s just a thinking machine.”

That is the temperament that is called for on the bench, and Hughes embraced it, although the Sun quoted him as joking in 1908, “I hope if an autopsy is ever performed on me, you will find something besides sawdust and useful information.”

Hughes came within a whisker of beating President Wilson, the incumbent, and was renominated to the high court by President Harding in 1921, and promoted to chief justice by President Hoover in 1930.

Justice Kagan, like Hughes, hadn’t served as a judge before her nomination, having been appointed by President Obama to the office of Solicitor General of the United States before he elevated her to replace Justice John Paul Stevens.

It’s easy to see why both jurists might chafe at putting on the black robe, a job that requires them to leave aside personal beliefs to apply the law as written, ensuring that justice is blind.

That’s the job each Supreme Court member accepts when he swears or affirms the oath to “administer justice without respect to persons and do equal right to the poor and to the rich, and … faithfully and impartially discharge and perform all the duties incumbent … under the Constitution and laws of the United States.”

This is the sacred mandate of the Supreme Court, not to stick their fingers in the wind to see which way it’s blowing. If Americans are dissatisfied with this role or outraged by an opinion, they can petition their elected representatives for relief.

The Nine, though, must be thinking machines, deaf to trending topics on Twitter, separate from the very “public sentiment” Justice Kagan invoked, filling themselves not with partisan political passions, but sawdust and useful information about the rule of law.